Unexpected Error

.

I began my residency at Woodford Academy expecting to be working with my hands—cutting, pasting, making sense of the past through layers of paper and glue. That’s still the plan. But I didn’t expect to spend quite so much time learning how to talk to machines.

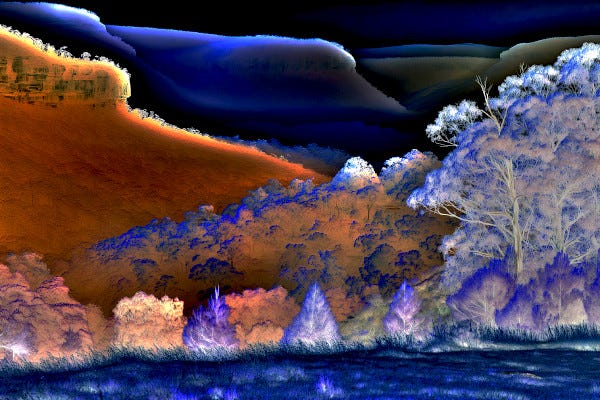

This past week has been a tangle of error messages, strange file formats, invisible colour shifts, and an ever-growing folder full of exported images that look almost right—but not quite. I’ve been trying to automate a digital print workflow: taking AI-generated images, scaling them properly, adjusting their colours for print, converting colour profiles, batch processing dozens of files at a time. It sounds straightforward when written like that. It isn’t.

I’ve never done any of this before. Not the image generation, not the coding, and not—significantly—the printing. Up until now, all of my collage work has been built from found ephemera: discarded magazines, old movie posters, half-forgotten paper trails. Everything arrived with its own patina, its own scars and history. I never had to make the image—I just had to find the right one, then cut it out.

But printing images from scratch introduces a whole new layer—one I hadn’t really anticipated. I thought I understood things like DPI, CMYK colourspace, gamma correction. I knew the terms. I could parrot the definitions. But I didn’t fully grasp how fragile and interdependent these things are until I tried to make them behave. I didn’t know how easy it was to ruin an image just by exporting it the wrong way. Or how subtle changes in colour profile could take something from luminous to lifeless in a single step.

There’s an inherent irony in much of my collage work. I often explore high-tech themes—data breaches, digital identity fraud, mass surveillance—but I do so using very lo-fi methods: essentially scissors and glue. That’s by design. It’s a feature, not a flaw.

But there was a moment yesterday—about six commands deep into a broken batch conversion—when I realised I had no idea what I was doing. Not in a despairing way, just… factually. I was copy-pasting commands into a terminal window, changing numbers, rerunning scripts, getting nowhere. The files were wrong. The colours were wrong. The output folder was empty. The error messages were cryptic, occasionally patronising, sometimes even flat out condescending.

Still, I kept going. I worked backwards, then tried again. I replaced tools, downloaded different software (that my antivirus software thought might be a bit dodgy), simplified the process, tweaked values. I learned, incrementally. Slowly. And I started to get results. Not perfect ones, but usable ones. Enough to keep going.

It’s frustrating work—tedious, at times—but also strangely addictive. There’s something satisfying about pushing through the murk of not-knowing and emerging, hours later, slightly less lost than before. I’m not sure I’ll finish everything I hoped to during this residency. The process is slower than I imagined, and more complicated than any tutorial made it sound. But I’m learning. I’m building tools I’ll keep using. And most importantly, I’m making things I’ve never made before—out of materials I didn’t even know were available to me.

This isn’t the work I thought I’d be doing. But it’s the work I’m doing now. And for better or worse, I think it’s taking me somewhere new and, to me at least, interesting.